.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Back

Next ![]() 16.2.2002 >>

15.3.2002

16.2.2002 >>

15.3.2002

"Wheel / Will"

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

IOn the edge of N’ve Zedek, under the recently

renovated Shlush bridge, is a long incision, marking the demarcation line

between Tel Aviv and Jaffa. On its southern side it parallels the Tel

Aviv-Jaffa Road, which changes its name to Eilat Street on its western

part. The no-man’s-land between the incision and the Tel Aviv-Jaffa Road

is a chaotic jumble of small mechanic shops, garages, wholesale and detail

fashion stores and textile sweatshops, forming part of the Tel Aviv

“schmate” district, cafes and restaurants (from the utterly squalid to the

aspiring), hardware stores, framing shops, Avni College of Arts, artist’s

supplies and what not. The incision itself marks the old Turkish railroad

tracks, which the municipality has paved and turned into a giant parking

lot (starting at the Romano House) and is now contemplating to transform

into a major West-East urban highway. Approximately in the middle of the

lot is an old one-story structure, built with roughly-dressed chalk stone,

one of the varieties of “Tubze” in Arabic. The Eskimos have fifty words

describing different kinds of snow, the Palestinian Arabs have fifty words

referring to various types of building stone. This is of the more simple

variety. The structure is one of the buildings belonging to the original

Turkish train station, one of the most ancient remains in modern Tel Aviv.

If you happen to park your car there at night (for free after 6 pm), you

see light in the dilapidated windows of the erstwhile train station, often

until the wee hours of the morning. This is the studio of Ziv Ben-Dov. If

you go in, you’ll see him, a slight-built muscular man, with head closely

cropped and face usually displaying a day’s worth of stubble, patiently

and relentlessly fighting clay into the shape that will, eventually,

reflect his vision. The studio, though very spacious, is cluttered with

chairs, desks, tables, students’ projects, wood constructions, paints and

brushes, finished and half-finished sculptures, jars and pots of various

glazes, drying used clay, wet mounds of reclaimed clay, fresh packages of

brand-new clay, and so on. The place has the unique blend of smells, of

dampness and dust, of wet clay, wood shavings, cigarettes, coffee and, of

course, the smell of cats that evokes my first impression of Tel Aviv in

the late fifties, when I arrived in this country. This is the true

trademark of old Tel Aviv.

Ziv was born in HaEmek hospital in Afula, 32 years ago. A native of

kibbutz Izrael. He did not finish high-school. In his own words, he did

not see any purpose in graduating. He always wanted to be an artist and

continued his studies in the Tel Hai Arts College. After the army service,

he returned for a short time to his kibbutz, then left for Tel Aviv and

began his studies at Bezalel in Jerusalem. “I was formally enrolled for

three years, but spent there four years. “How did you get in? Without

matriculation exams?” I ask. “There are always a few slots for students

who did not graduate from high-school, and I did well on the entrance

exams” he says. Though outstanding student and a winner of a number of

prizes, he did not graduate. Once again, he saw no purpose in any formal

definition of his studies. “I enjoyed Bezalel very much, and I stayed as

long as I could learn and absorb things that were good for me. I spent a

lot of time in the Bezalel cafeteria, looking in from the outside. I owe a

lot to some of my teachers. Not so much as art teachers, but rather as

people.” He mentions Larry Abramson and Gaby Klasmer. “I saw myself as

observing from the cafeteria, not in one of the Departments.”

Ziv defines himself as an extra-terrestrial, watching reality from outer

space, a free student in the cafeteria. At any moment he might nip into a

class that he finds interesting. His art is an effort to define his own

self versus the total reality. If it happens to be of interest to others,

it is in a context of a personal statement about his encounter with

reality.

When he answers questions, it is with some difficulty, trying to choose

the right words and the correct syntax. He often pauses in mid-sentence,

to begin again in a more precise way. After many attempts to define his

position vis-?-vis the art scene, he gives up. Instead, he suggests two

very short stories that he wrote. Although they do not present explicitly

his views on art, they give an insight into Ziv’s personality. They are

brought verbatim in the boxes within this article, though they lose some

of their poetry in translation. Ziv’s ears are listening all the time to

voices from heaven and from earth, while he is suspended between the two.

He is also “Thin” the snail, waiting for the music of silence to come out

of his shell.

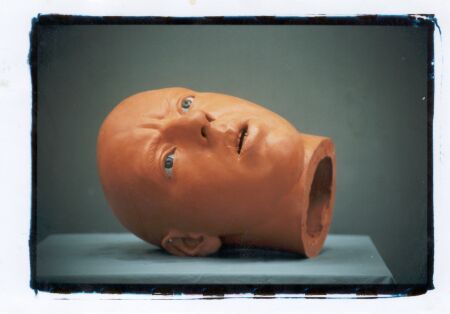

On this background, what is Ziv’s art? He works mostly with clay (“But not

only clay” he corrects). All his sculptures are figurative and highly

realistic in detail. He spares no effort, takes no shortcuts, doesn’t

bluff or take the easy road towards the overall impression. His most

recent work, a man kneeling on one foot and staring at the world through

his palms and fingers forming child’s-fantasy binoculars, is a good

example of his disdain for compromise. The hands are added after the head

is completely formed and, practically cover the eyes and the eyebrows.

Yet, when the hands were still missing, the eyes and the eyebrows were

executed to the same standard of perfection as any other aspect that is

indeed visible in the finished sculpture. It is clear that “fudging” in

areas that you might not see will not only offend his pride (of which

there is very little evidence), but seriously detract from the purpose of

the work, of the absolute fidelity to the concept. I have seen Ziv re-do

several times the eyes of one of his sculptures, until he was satisfied

that it was not necessarily the best, but at least the best he could do.

He is interested in video art. He invested a month in building the props

for his three-minute sequence, several sessions of rehearsals with the

model and abandoning it all when the final product did not satisfy him.

Than he spent another few weeks, building a different prop. This time it

was a giant wood, metal and plywood wheel, designed to house the two

actors (himself and a woman model) with a special contraption that moved a

tightly stretched piece of fabric to breathe in and out with the turning

of the wheel, to create the feeling of a pump, alternately making and

filling a void between the two people facing each other head-to-toe on

this wheel of encounter. This was also abandoned after the final shooting.

Who is his observer with his hands-binoculars? The model is Ziv himself,

slightly less than life-size. He is frozen, intent in his amazement and

curiosity. He is looking at the outside reality without participating in

it. Actually, although he is trying to observe the world with his

hands-binoculars, all he can see are the hands themselves. There is a

compactness and tenseness in his posture. Even though the veins on his

hands, the folds of his clothes and even the soles of his heavy rubber

soles are executed in a painstaking realistic fidelity, the situation, the

stance invokes the surreal, or perhaps the unreal. His frozen perfection

is disturbing and begging for explanations.

Two of his works that I am familiar with are my favorites. One is a very

large fiberglass cast. Several people are assembled at the vast worktable

in the studio. The table and the figures were covered with one enormous

sheet of material and the whole tableau was cast in a shell of fiberglass.

Later, the entire surface was covered with yellowish sand, glued to the

surface. The sculpture is very silent and eerie, again completely

realistic and yet unreal. Who are these figures under the enormous shroud.

Are they a secret conclave deciding weighty questions in absolute secrecy?

Or are they rather watching introspectively, cutting themselves

purposefully from the outside world? For almost a year this very large

work was hanging from the beams of Ziv’s studio on makeshift pulleys and

ropes, posing a not-so-vague threat to every visitor. Finally, Ziv cut it

into four sections and re-assembled it on the studio roof. You can get an

excellent view of it from the other side of the parking lot, if you dare

the goat path that leads there. Ziv is scarcely aware anymore that it is

there. “Maybe I made it before its time” he says, half jokingly, but also

half seriously.

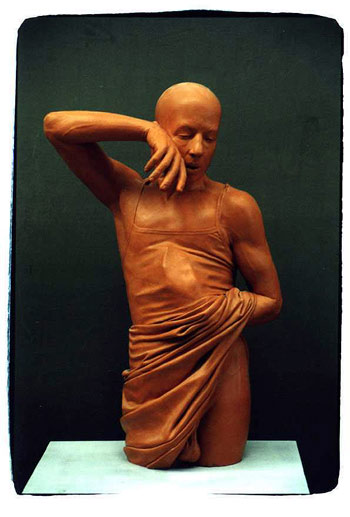

Another favorite of mine is a clay sculpture named (by Ziv) “My sister”.

This is again an self-portrait. A younger Ziv, head shaved and with a

slightly more elongated neck and more graceful figure, gazes intently and

longingly at the world. One arm, bent in a ritualistic gesture, part of

the palm and fingers melting into the “Sister’s” cheek. The other,

imitating that of Michelangelo’s Adam, approaches it from below. The

figure is draped in a tightly fitting shift, the clinging material

stressing the femininity of the subject. The impression is jolted by the

figures testicles, which escape partially from under the raised gown. The

immobilized flow of the sculpture sends many conflicting messages. It is

very sensual, frankly sexual even, but at the same time innocent and

immature. The feminine aura contrasts with the male appendages. The

sensual curiosity of the gaze is also turning inward, partly in delight,

partly in amazement and partly in question. This implied hermaphrodite is

deeply disturbing, in my mind putting a question mark on sexual

stereotypes, on the viewers relationship to himself, and through himself

to the female. No matter how many times I have seen it, it never fails to

attract me anew.

“Why clay?” I ask. Ziv’s answer is that it is a result of a chance

encounter. But it turned out well. Because it is fluid and amorphous,

malleable, does not present a shape of its own. On the other hand, it can

be worked into a most defined and realistic shape. And the accompanying

processes, says Ziv, are very likable. The physical and chemical

transformations, from almost fluid to hard and brittle upon drying, then

to rock-hard when it’s fired. Yet Ziv works not with the clay, utilizing

its natural tendencies, but rather against its character. He is trying to

achieve an effect of no medium, to hide the material and its claims and

leave the message alone. For the “presence” that he demands from his

sculptures, the material should be absent, creating a medium of the least

possible resistance, to be a pure conducting device, as a low-resistance

wire is for electricity. His attitude towards his own work is that of a

worshipper in an almost religious sense. What he is trying to do is to

distill a certain presence and to achieve purification through it.

Being an “extraterrestrial” makes him a manifest outsider. “What will

happen if you’re ‘discovered’ one day?” He thinks for a few moments. “I

will most probably retire. I will feel a pressure to deliver the goods.

This is not from ideology or any feeling of superiority, but inability to

perform under pressure.” “You’re married, with two children, and you

require money for materials, some of them quite expensive. What if you

wanted to do something very expensive, a monumental sculpture in bronze

for an instance?” But Ziv does not feel he is in any way handicapped by

money. “If I want to do something very expensive in the future, I believe

I would be able to get the means for it. I’ll find a way.”

Ziv likes to teach. He gives ceramic sculpture classes to students who

have been working for years and to those who have no background

whatsoever. He is never didactic, neither openly critical. He finds good

points in every students work and his remarks are very tenuous and

constructive. Yet, somehow, people that you would never suspect of having

any aptitude for sculpture, find the artist in their soul and pour their

personality into their pieces. Like “Thin” the snail, the music of silence

in Ziv’s classes makes them come out of their shells. Those who prefer

structured teaching, methods and technique, disappear after a class or

two. The ones that persevere form a widely different group from age twelve

to sixty, from kindergarten teacher to high-tech executive, different in

all aspects, except for their enchantment with listening to the voice of

the earth and the voice of heaven and trying to translate the crossing

messages into clay creations. The class size fluctuates from day to day.

One day ten students, the next only two. But there are students who

participate on and off for years. It is not a class in art in a strict

sense of the word, neither it is group therapy (though it may sometimes

appear as such). But if you can adapt, like clay, to this undefined mould,

you find that after a while you see art and life differently and enjoy

both more. Like Ziv and his sculptures, you acquire the “extraterrestrial”

skills of looking at the world through your own binoculars and keep the

curiosity of an observer that is amazed each time that there is infinity

of shapes to discover.

“The encounter”

I was a young boy when we set out to ride our horses in the Jezrael

Valley. We were galloping, Mouli, Zevulun and I. The horses were competing

for a ditch camouflaged in a watermelon field. Zevulun and I crossed the

ditch in flight, while our horses stumbled and rolled on the ground.

Mouli, slightly behind us, spurred his horse over the ditch. On the ground

my diaphragm was received by a watermelon, apparently trying to bypass the

initial stages of digestion. The sudden encounter left me with my mouth

wide open, curled on my side, in vacuum, trying to reconnect the broken

edge between the field and the sky, to form one picture of the view

presented to my two eyes.

Ziv!? Ziv!? The hesitating sound of steps coming to the ear pressed to the

earth, and the two voices calling each to the other in the sky, and I in

the middle, as a mediator.

“The way”

“”How”, who was a small child, wanted to train “Thin” the snail. He put

him down and called from above “Thin, get out! Emerge into daylight!”

“Thin” immediately and utterly shrank into his spiral lair. And so it

continued, an unsuccessful parade exercise. “Thin” getting more thin and

compact, and “How” more upset. Finally, “How” got tired of persuading the

snail’s shell, and only silence was left, a strange music that completely

changed the scene.

Slowly, slowly, he saw a glance, his feelers groping from inside. Here he

is, not anxious anymore, his mucus posterior appearing and leaving

embroidery of glistening trail. That’s the path of “Thin” and the way of

the world.